| Period | Sunday, June 28 - Sunday, November 8, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Closed | Mondays (except for National Holidays / the following Tuesday instead) |

| Opening Hours | 9:30 - 17:00 (last admission at 16:30) November:9:30 - 16:00 (last admission at 15:30) |

| Admissions | Adults 600 (550) yen, Junior High / Elementary School Students 300 (250) yen *( ) indicates prices for groups of 20 persons or more. Seniors (over 65years old) 300 yen (Please show proof age.) |

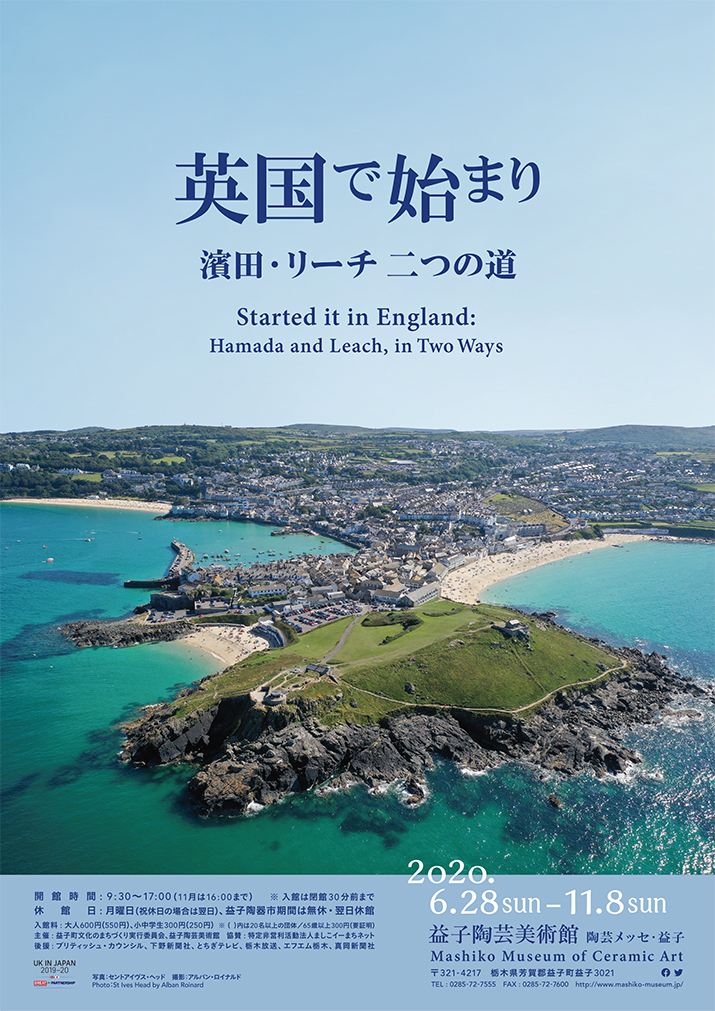

The exhibition, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Leach Pottery, introduces the development of British studio pottery from around 1920 to the present and that of Mashiko's studio pottery starting from Hamada.

There will be three sections: 1. The Dawn of Studio Pottery (featuring the early period of the Leach Pottery) / 2. The Attraction of British Studio Pottery (from 1920s to the present) / 3. Studio Pottery in Mashiko (unknown aspects of Mashiko pottery). It will be a kind of culmination of what Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art did in these 25 years and probably will be a first show in Japan focusing on how the consciousness of studio potters grew up.

We are going to show Japanese and British 170 pieces of 60 artists together mainly from our collection and add some from other museums in Japan. One of the highlights is early pieces from Hamada's first solo exhibition in 1923, from the ceramics collection of Aberystwyth University.

|

|

| Hamada Shoji Vase 1923 School of Art Museum and Galleries, Aberystwyth University Ceramics Collection, |

Bernard Leach Raku plate 1919 Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art © The Bernard Leach Family, DACS & JASPAR 2020 E3749 |

|

|

| Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke Small bowl, marbled decoration c.1924 Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art |

Michael Cardew Pie dish with heron design 1928 School of Art Museum and Galleries, Aberystwyth University © The Estate of Michael Cardew Ceramics Collection, |

|

|

| Kamoda Shoji Bowl with curving incised pattern 1970 Yanagisawa Collection |

Kimura Ichiro Lidded box with inlaid pattern 1940 Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art |

|

|

| Hans Coper Pot 1975 The Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo |

Edmund de Waal things exactly as they are 2016 Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art |

Yokobori Satoshi

The history of Mashiko ceramics is said to have begun in 1853, when it split from the nearby Kasama pottery center. Kasama ceramics used technqiues learned from unemployed Shigaraki craftsmen floating around other production centers. In Mashiko, adjusting those Shigaraki techniques to suit the Mashiko clay, its potters produced ordinary rustic ceramics. Despite its brief history and its location in a country town in the rather remote northern part of the Kanto region, in the mid 1920s, Mashiko did not lag behind other pottery centers that had far longer histories in producing studio potters. A major reason for that development lay in Hamada Shoji's return from Britain in 1924.

Upon returning to Japan, Hamada headed straight for Mashiko, which he had recalled when he visited the Ditchling craft community in Britain. He had used used the character 庄 ("Sho") taken from his name as his signature on the works he produced while in Britain. Upon moving to Mashiko, however, he stopped signing his work. Yanagi Soetsu explained the reason for that change as follows:

Why would you call work like pottery, work in which powers that transcend those of the human being operate, as if it resulted from the efforts of just oneself? In modern times, almost everyone has been signing work, but that custom did not exist in the past.... Why can you not return to that nameless state and create work from there?1

Hamada did not seek to source high quality clay from elsewhere. Instead, by making effective use of Mashiko clay, he developed ceramics possible only in Mashiko. To Hamada, Mashiko clay was not inferior.

At first, not having his own home yet, Hamada went back and forth frequently between Mashiko and Okinawa. He learned much from Okinawa's unsullied culture. Okinawa lies at an intersection between East and South Asian civilizations, and the distinctive Okinawan culture born in that context captivated Hamada. Through his experiences in Okinawa and Britain, Hamada changed his pottery's direction from his earlier preference for ceramics in Chinese and Korean styles; he found the direction in which he himself should proceed. While he reoriented his work, he did not do away with all he had learned in the ceramic arts. Rather, his adding British elements produced something new. For example, the linear slipware motifs with which he experimented in Britain combined with the knowledge and experience he continued to amass led to the creation of his nagashigake (poured slip) technique in the mid 1950s.

In 1930, Hamada built a house and climbing kiln in Mashiko and began producing ceramics there in earnest. His work sold well, partly because of the influence of the Mingei (folk craft) movement, in which Hamada was involved, and many other potters in Mashiko began to make similar wares. The result was a major change in their output, so much so that Mashiko ware might well be termed "Hamada ware." That term was not in widespread use, but in the mid-twentieth century, Mashiko was awash in ceramics that were imitated Hamada's.

After the war, many young people aspiring to become potters came to knock on Hamada's door. Murata Gen, Shimaoka Tatsuzo, Takita Koichi, Abe Yuko, and Hamada Shinsaku were all potters who studied with Hamada in his early period and shared not only his techniques but also his spirit. It is thus possible to call the potters who studied with him in that period the "Hamada school."

For example, for ceramic arts like Murata's that were dependent on the Mashiko clay, Hamada proposed, "It is my belief that when you discover a place with a natural clay that suits your work, you should have your own studio and kiln there."2 Indeed, Murata's work was deeply connected to Mashiko clay. Shimaoka dedicated his life to perfecting the decorative technique known as Jomon inlay patterns, a success rewarded by his following Hamada in being designated a Holder of an Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure). Takita's concept was white porcelain with warmth, not white porcelain that seemed so sharp it could almost slice your hand open. Yanagi Soetsu and Hamada recommended Takita, who had academic inclinations, to teach at Pakistan's National College of Arts, and he spent three years in South Asia. The folk cultures he encountered there became part of his style. Abe, after completing his training in Mashiko, brought his pottery to maturity in Kyushu through participating in the Mingei movement. Hamada's second son, Shinsaku, followed his father in hewing to the Hamada pottery glazes and clay, while creating tranquil works that differed from Shoji's dynamic style.

Claiming that studio pottery sprouted in Mashiko because Hamada chose to work there oversimplifies its history. Another key figure was Kimura Ichiro, who was from a wealthy local Mashiko family. While in middle school (under the prewar system; roughly junior and senior high school) he experimented with making ceramics with friends from potters' families. We can well imagine that Kimura, having been born into an affluent family, also found his interest piqued by the Nihonga paintings and craft objects that decorated his home. As he learned to appreciate the work of Kawai Kanjiro and other ceramic artists, he decided that he would overcome his family's opposition, come what may, and become a potter. His family operated a local post office, and through a post office connection, Kimura was able to enroll at the Imperial Ceramic Experimental Institute in Kyoto3 to study the ceramic arts. Originally the Kyoto Ceramic Research Institute, it was, at that time, the heart of modernization in the arts and crafts in Kyoto.4 In describing the institute, Kiyomizu Rokubei V, head of the Kiyomizu family of Kyoto-based potters, said, "The opening of this testing institute and its vigorous activities have stirred up a striking response in the Kyoto ceramics industry, which had long been engrossed in producing only conventional wares."5 The Kyoto potter Yagi Isso, who trained at the institute, was also a member of Sekido, the avant-garde group of ceramic artists that Kusube Yaichi, his classmate at the testing institute, had founded.

Unlike Mashiko, a pottery-producing center in the countryside in the northern Kanto region, Kyoto was home to a crafts world with long traditions in which, as the statement by Kiyomizu Rokubei V above makes clear, a movement to break up the old, conventional mode of production and aim for a new, even revolutionary ceramic arts had already begun. That same period also saw, with the formation of the Association for the Creation of National Painting, a movement directed at changing the stodgy Kyoto art world and calling for a new Nihonga (Japanese-style painting).6 Isso's son Yagi Kazuo's avant-garde thinking in founding the Sodeisha in 1948 was aimed at achieving a new ceramic art, as though Kazuo was carrying on his father's intentions. That movement also led to the formation in Kyoto of another avant-garde ceramics group, the Shikokai.

Kyoto, where all these new things were happening, was where Kimura became interested in Yagi Isso; he also was a classmate of Yagi Kazuo at the training institute. Moreover, in May 1937, Kawai Kanjiro won a Grand Prix at the Paris Expo. When Kimura was helping load the climbing kiln on Gojozaka in Kyoto, he must have had opportunities to observe Kawai close at hand. Those experiences, those encounters with progressive trends in Kyoto surely stimulated Kimura. He returned to Mashiko as something of an enfant terrible and set about developing ceramics that had never been seen in Mashiko before.

After the war, Kimura, having completed his military service and returned to Mashiko, built a climbing kiln in 1946. Hamada is said to have been present each time Kimura unloaded his kiln. Perhaps he felt an artistic quality different from other Mashiko potters' in Kimura's ceramics.

For some reason, however, Hamada seems to have had a negative attitude towards Kimura's shinsha (copper-red glazed) and neriage (marbled clay) wares. Why is unclear, but, in Mashiko, Hamada did not apply the shinsha and neriage techniques that Kawai Kanjiro used extensively. Kimura experimented in many ways, creating vessels using delicate slip trailing designs on galena lead glazes, neriage works, shinsha glazes, and glass glazes. There were so many types of ceramics that he wanted to try making that he could not attempt them all.

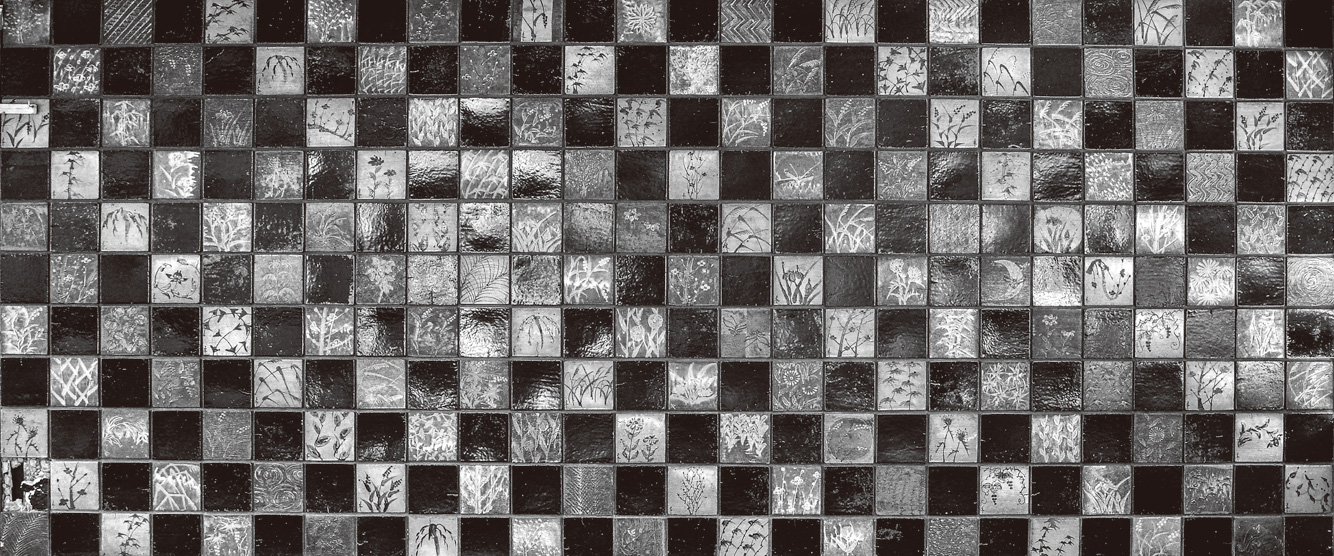

Fig. 1 Ceramic Mural by Kimura Ichiro, ca. 1965.

Kimura's pioneering work at Mashiko included creating a ceramic mural (Fig. 1) in about 1965, when such works were not yet common; this and other experiments were loudly criticized by the ignorant around him. His early work includes the use of delicate lines and dots formed by slip trailing, as can be seen in his Kyoto-period work, for example the Set of Small dishes with slip trailing, amber glaze (No. 144), which are quite flawless. In the year after he returned to Mashiko, he also produced the Set of Square dishes with marbled decoration, amber glaze (No. 145), using the neriage marbled clay technique for which there were no prior examples in Mashiko. Similarly, he was the first in Mashiko to use the shinsha copper-red glaze.

Was, then, Kimura a studio potter operating in a different context from Hamada? Let us examine the exhibitions that were Kimura's main fields of activity at the time. In the Fourth Contemporary Ceramics Exhibition (1955), he showed his Black Glazed Square Bowl with Resist Decor and Large Dish with Grasses. The potters in that exhibition included Kawai Kanjiro, who had deep ties to Mashiko, the Kyoto potters Uno Sango, Kiyomizu Rokubei, Kusube Yaichi, Hayashi Yasuo, and Kondo Yuzo, the Seto potters Kato Mineo (Okabe Mineo) and Kawamoto Goro, and the Hagi potter Sakakura Shimbei, as well as Kato Tokuro, Kato Hajime, and Fujimoto Yoshimichi.7 In the Sixth Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition (1959), he was awarded an Encouragement Prize, as were Kato Mineo, Yamamoto Toshu, Nakazato Tarouemon, Tsuji Shimbei, Sakakura Shimbei, Tsuji Shinroku, and Hara Kiyoshi. Kaneshige Toyo, Hamada Shoji, Uno Sango, Shimizu Uichi, and Ohi Chozaemon all adopted the same stance in showing their work.8 Kimura's work in that exhibition, by the way, was his Iron-Glazed Faceted Jar. In the Contemporary Japanese Ceramic Art exhibition9 held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, starting May 23 of that year, Kimura was asked to exhibit, and showed his Neriage Style Jar. That major exhibition provided an overview of contemporary Japanese ceramic arts, dividing them into into the Nitten school, the Shinshokai, the Mingei school, the avant-garde school, the Japan Kogei Association, and others. Kimura was of course selected to exhibit. He was also asked to show work in the International Exhibition of Contemporary Ceramic Art, which opened at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, on August 22, 1964, and traveled to the Ishibashi Museum of Art in Kyushu, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, and the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art in Nagoya.

Kimura's activities in about 1955 to 1964 were quite amazing. Why was it, then, that his name does not appear in exhibitions from 1965 on? In 1965, when the term "ceramic mural" was still unusual, he created a ceramic mural and also received the honor of an order from the Imperial Household Agency, Crown Prince's Palace, for Large Square Bowl with Snowy White Glaze and Square Dish with Bamboo in Falling Snow.10 It was also that year that Kimura resigned from the Kogei Association. That was perhaps because, it is said, someone in the association had said to him, about his Neriage Jar, "Isn't that stonework?" Ironically enough, the Ibaraki prefecture ceramic artist Matsui Kosei, who was later designated a "Living National Treasure" for his neriage work, had learned the basics of neriage from Kimura. Having left the Kogei Association, however, Kimura's name soon vanished from center stage in Japan's modern ceramic history.

Another potter who must not be forgotten is Kimura's apprentice, Matsubara Naoyuki. Armed with a name card Kimura had given him, Matsubara called on Yagi Kazuo in 1958. After a year of working under Yagi, Matsubara had grown so thin that Yagi, worried about his health, invited Matsubara to become a live-in apprentice, living and working at Yagi's home. Matsubara then concentrated for two years on assisting Yagi in creating ceramics. To fire Yagi's black earthenware, he had to haul the pieces in a two-wheeled trailer to Yagi's father, Isso. Each time he made that trip, Isso shared a Kyoto-style meal with him; there was, Matsubara said, no greater joy. His experiences in Kyoto and his becoming aware of ceramic artists there inspired him to develop his own individual style. After three years of training in Kyoto, Matsubara returned to Mashiko and perfected his own mode of expression in ceramics, working in a namijiro white glaze that did not imitate Hamada's work.

In about 1960, the Tsukamoto pottery, located in Fukada, Mashiko, set up a training system, and a steady stream of young people with dreams of becoming potters came to Mashiko to begin their careers. During the day, they worked on massproduced items at Tsukamoto, but they were permitted in their own free time to make whatever sort of pottery they liked. They learned throwing on the potter's wheel, methods for preparing glazes, and firing techniques from old timers in Mashiko. And Tsukamoto even provided housing. Had that training system not existed in Mashiko, Hamada probably would not have been able to train the next generation. Back then, most people in Mashiko were poor and made their living half by farming and half through ceramics. The establishment of the Tsukamoto training system was a game-changing event that meant that young people from other areas who hoped to become ceramic artists moved there. Mashiko, which had a brief history compared with traditional pottery centers, had had only a very few potters, such as Hamada Shoji and Shimaoka Tatsuzo, who had the means to take on apprentices.

One characteristic of the generation following Hamada was their educational background: many had graduated from art schools or universities. (Of course, the Tokyo Technical Higher School, from which Hamada Shoji himself had graduated, later became the Tokyo Institute of Technology.) Kamoda Shoji, who graduated from the Kyoto City University of Arts; Seto Hiroshi, who studied there later than Kamoda; Hirosaki Hiroya, who was moved by Hamada's work while at a university in Tokyo to decided to become a potter; Yoshikawa Mizuki, a member of the first class at Tokyo University of the Arts' new ceramics program: these potters who would become Hamada's successor generation moved to Mashiko. Apart from Yoshikawa, whose experience working as an engineer at the Tochigi Ceramic Industry Training Center, in Mashiko, inspired him to create ceramics, all had come to Mashiko as trainees at the Tsukamoto pottery.

Given that Kamoda Shoji graduated from the Kyoto City University of Arts, can he be included in the Kyoto school of ceramics that Kimura brought to Mashiko? Kamoda had found employment at Omika Ceramics, which was part of the Hitachi, Ltd., factory in Ibaraki prefecture. That led to his coming to Mashiko, because Kimura Ichiro and Karashima Jun'ichi, who was head of the ceramic insulator department at Hitachi, were acquaintances. Hitachi had been purchasing Kimura's ceramics to use as gifts. Then someone came up with the idea that Hitachi should make its own gift ceramics, and Omika Ceramics was founded at the Hitachi factory. An announcement that it was hiring technicians to produce art ceramics was sent to the Kyoto City Art Museum, and Kamoda and Takeuchi Akira, who had been ahead of Kamoda at the same university, found jobs as technicians at Omika Ceramics in Ibaraki. Kamoda then had a meeting with Karashima and Kimura, arranged by Karashima, and was allowed, as an exceptional concession, to take a leave from his work at Omika and stay in Mashiko as a trainee at the Tsukamoto pottery. Karashima served as the gobetween between Kamoda and Kimura. When he first arrived in Mashiko, Kamoda rented a detached unit of Kimura's house. It may be that Kamoda saw studio potters and a production format similar to the studio pottery in the Mashiko potteries, which included many family-based operations producing on a small scale.

Then, wishing to move permanently to Mashiko, Kamoda formally resigned from Omika Ceramics and began making ceramics as a living. His efforts opened up unprecedented new terrains in the ceramic arts. In 1970, he fired his Kyokusen chomon (curving incised pattern) works using clay from Tono, in Iwate prefecture, works that, an ultimate in ceramic expression, are still the stuff of legend today. The basis of Kamoda's ceramics is yakishime, unglazed, high-fired wares. But his are not merely unglazed. He coated the surface of each piece with a highly refractory clay, then scraped it off after firing to create a remarkable texture, a sense of the clay. Starting around 1970, Kamoda changed the motifs with which he decorated that surface every year. His fans, looking forward to those changes, would line up at the entrance to the gallery where his solo exhibition was to be held the day before it opened.

Seto Hiroshi, who studied at the Kyoto City University of Arts somewhat after Kamoda, moved to Mashiko and began producing ceramics there. But, inhibited by the exalted presence of Kamoda, he found himself unable to create ceramics free of Kamoda's influence. Seto then received an invitation in 1970 to go to the United States. Through his experience there, he became one of the potters bringing an innovative, even radical air to Mashiko. His ceramics probed the relationship between vessel form and motif, moving from linear incised motifs to specialize in smooth gold and sliver stripes. His creating ceramics as pure sculptural objects, not vessels, as in his Striped ring (No. 168), was highly significant.

Hirosaki Hiroya pioneered creating porcelains, rather than using the local clay, in Mashiko. His were not, however, conventional porcelain vessels. The ivory-colored porcelains he named Gehakuji (No. 169-171) epitomize his distinctive creative world. Amidst his difficulties in creating in his own unique way alongside the nationally acclaimed potters Hamada and Kamoda, he was able, by working in porcelain rather than clay and creating his ivory jars, to build his own domain.

Yoshikawa Mizuki, an elite graduate of Tokyo University of the Arts, became an instructor at the Tochigi Ceramic Industry Training Center, then became an independent potter. Applying his extensive knowledge of chemicals, he improved the Mashiko black glaze and, in his late period, succeeded in firing the black glaze with the fascinating melt-inyour-mouth quality that he had been seeking throughout his career. The floral motifs that seem almost to have dissolved in the black glaze make one think that the phrase "unfathomable profundity" was coined to define Yoshikawa's ceramic art. These artists, the generation following Hamada, brought a second Golden Age to Mashiko. Talented people with an ambitious commitment to the importance of ceramic art gathered here. They included Yasuda Takeshi, Kotaki Etsuro, Koinuma Michio, Sakata Jinnai, and others who could not be introduced in this exhibition.

The history of modern ceramics includes the emergence of studio pottery in Britain. But can we not say that another studio pottery tradition, apart from studio pottery in the Western context, existed in Japan? How, for example, can we explain the ceramics, such as those created by sixteen generations of the Raku clan? Didn't each Raku potter in each generation have his own individual style? Each and every human being has his or her individuality; it is because they have that individuality that they are human. The ceramics that human beings create must necessarily reflect that individuality. Individual, original ceramics were being created before the emergence of the ceramic artist as seen in the history of modern ceramics. In those works we sense the establishment of distinctively Japanese creative qualities. In premodern Japan, moreover, terms equivalent to "ceramic artist"‒and people to whom they applied‒already existed. When Chojiro, the first generation Raku potter, began producing Raku ware in the latter half of the sixteenth century, his tea bowls, shorn of all decoration, were called ima yaki, "now ware." It is not hard to imagine that they were felt to have cutting-edge, avant-garde qualities. Instead of simply carrying on traditional styles, the Raku clan has continued to create ceramics in which each potter reflects his own age's sensibilities and creates a new now in his generation. As the Raku example indicates, individual creation has long existed in Japan. What is tradition, after all, but an accumulation of individual innovations?

(Curator, Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art)

Notes

| 1 | Hamada Shoji, Kama ni makasete (Autobiography of Hamada Shoji), Nihon Tosho Center, 1977. |

| 2 | Bernard Leach, Hamada Potter, Kodansha International, 1975. |

| 3 | The former was the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute, where Hamada Shoji and Kawai Kanjiro were the members. It was raised to the status of a national institute in 1919. |

| 4 | Maezaki Shinya, Taisho jidai no kogei kyoiku (The Craft Education in Taisho Period), Miyaobi Publishing, p. 5, 2014. |

| 5 | Ibid., p.6. |

| 6 | Matsubara Ryuichi, "Yagi Kazuo no kiseki (The Path of Yagi Kazuo)," Yagi Kazuo A Retrospective, Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Inc., 2004. |

| 7 | The 4th Contemporary Ceramics Exhibition catalogue, Nihon Kogei Kai, 1955. |

| 8 | The 6th Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition catalogue, 1959. |

| 9 | The Contemporary Japanese Ceramic Art exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Modern Art, 1959. |

| 10 | "Kogosama no gochumonhin (The Order of the Empress)," Shimotsuke Shimbun, 23rd April, 1965. |

*"No." means plate numbers in the exhibition catalogue

Matsuzaki Yuko

"Studio pottery" refers to pottery as creative expression, produced in the studio of an individual potter or in the company of a small number of potters. It is not pottery mass produced in factories. More strictly defined, studio pottery refers to a crafts movement that developed in Europe and America in the early twentieth century, advanced by a generation who had been trained at art schools. Bernard Leach, the founder of British studio pottery, presented his vision of "a marriage of East and West" as his fundamental concept. The origins of that vision go back to the 1910s, before he returned to England. Leach had encountered Raku ware in Japan, became fascinated there by examples of his own country's slipware tradition, began studying Song and Goryeo celadons and ceramics, and made them his standard of beauty.1

In 1913, two years after he began learning to make pottery with Ogata Kenzan VI, he was introduced Lomax's Quaint Old English Pottery by Tomimoto Kenkichi, and became enthralled by the world of slipware. Just before returning to England, he fired Raku Plate (No. 3) at the Tomon kiln built at the residence of Kuroda Seiki in Azabu, Tokyo. In its green letters and motifs we can glimpse the influence of English Toft ware.

Leach's earliest work was very much for artistic appreciation, not functional ware.2 From the mid to the late 1920s, based at the Leach Pottery in St Ives, he presented superb, richly colored Raku-ware works in the Delft tin-ware style together with decorative galena lead-glazed, slip-trailed dishes. (The latter works are probably why the identification of Leach with slipware is so strong in Japan.) Leach's interest was shifting, however, from highly decorative soft-fired pottery to high-fired, vitrified stoneware, regarded at the time as both functional and noble. The Leach Pottery made stoneware production its center of gravity. The stoneware decorative tiles on which Leach exercised his talent for painting have been highly regarded since he first produced them. His Tiles with iron painted decoration (No. 8) features a pattern composed of motifs that were Leach's forte (willow tree, flora and fauna, jar, climbing kiln, well). It epitomizes Leach's decoration.3 He was indeed a painter who developed a brilliant style for painting his pottery. What he had discovered in pottery as a medium, however, was pattern that harmonized with material and form. That was, it should be noted, quite different from painting based on painterly concepts.

In the West, the period from the latter half of the nineteenth century to the 1920s was one in which the reigning concept of the arts was shaken. In Britain, asserting the autonomy of the arts and asserting the intersection between art and society were two positions that emerged. The latter is associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, which originated with John Ruskin and William Morris and also inspired the birth of artists' villages in Britain. The context in which studio potters, including Leach, were born was related to those movements, specifically the question of hierarchy between the art and craft genres. Raising the position of ceramic arts and other craft arts, positioning the crafts as art, questioning the nature of mechanized labor and modern industry, and a rising awareness of material culture and the nature of the object: all these trends were emerging simultaneously.

While there are various theories about studio pottery's origins, it is agreed that it dawned at the end of the nineteenth century. Today, the works those earlier potters are referred to as "art pottery" to distinguish them from Leach and the other studio potters who emerged from the 1920s on.4 Their work is related to studio pottery in its orientation to creative expression in forming and firing, but their production was in the handicraft industry manner, using a division of labor. Those potters thought of their "designs" as capable of mass production. Those aspects distinguish the artist potters from studio potters. The Martin Brothers (active 1873-1915) were emblematic transition-period potters. Their minute, somewhat grotesque designs, as seen in Vase (No. 34) and Bird (No. 35) display the aesthetics of Japonisme and the Victorian age.

In the 1880s, however, the standard for judging the beauty of ceramics was gradually shifting from painterly decoration to the character of the clay and the techniques used. In terms of historical context, the importation of the values of the Japanese tea ceremony was significant.5

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, many Japanese works of art, including tea utensils, flowed overseas, and Bizen, Shigaraki, Oribe, and other ceramics used in the tea ceremony were acquired by collectors in the West. The rustically simple beauty of their glazes and forms were praised, and even influenced, indirectly, the late-period work of the Martin Brothers. Early in the twentieth century, Okakura Tenshin's Book of Tea was published and was introduced in The Studio, an influential magazine specializing in the fine and applied arts. In addition, construction of railways in China in the latter half of the nineteenth century led to discovering many examples of high quality Song-dynasty ceramics, which fascinated Europeans. In Britain, the Burlington Fine Arts Club in London held an exhibition of antique Chinese ceramics as early as 1910. R. L. Hobson, keeper of the Department of Ceramics and Ethnography at the British Museum, and major collectors became passionately devoted to them. While Chinese ceramics became well known on continental Europe somewhat later, they were a major influence on highly aware potters, quickly giving rise to new interpretations of forms and glazes.6

Early studio pottery's foundation was the aesthetic provided by Japanese tea ceramics, but the influence of Chinese ceramics was also conspicuous. Vessel forms were plain, and, instead of the showy and realistic decoration of the previous period, abstract styles presented through the glazes and use of sgraffito were highly regarded. One of the most important artists of this period was William Staite Murray. While Leach considered vessels' practicality and the ethics of creating ceramics, Murray regarded the vessel as sculpture, frequently gave his works titles, and showed his work in galleries along with paintings. That is, Murray saw himself as participating in the "art world" by means of ceramics. Reginald F. Wells originally produced slipware, inspired by English ceramics from the seventeenth century, but, in response to the 1910 exhibition mentioned above, switched to working in the manner of Chinese ceramics. He gave his ceramics the trademark "SOON," and produced works such as Vase (No. 37), which is eminiscent of the Jun ware with purple marks on celadon glaze that early studio potters admired. Wells, a pioneer who put great effort into controlling his materials, produced many experimental works.7

Murray became professor of ceramics at the Royal College of Art in 1925 and later head of its ceramics department. (His influence in training later generations was enormous; the Royal College of Art went on to produce many artists who identified as ceramic artists or ceramicists.) While he was seen as Leach's rival, he built friendly relations with Hamada Shoji, and Hamada taught Murry hakeme (brushmark slip) and techniques for making bottom rims of ceramics vessels.

Hamada Shoji himself was a key person in early English studio pottery. William Winkworth, a British Museum curator who saw Hamada's solo exhibition at the Paterson Gallery, stated in a letter to Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke that he was impressed by Hamada's hakeme works and, while expecting the use of more characteristically Japanese techniques, recognized Hamada Shoji's individuality as an artist and the budding of the "Hamada style" (ref. material no. 6).8

Hamada Shoji, in his contributions to the diffusion of East Asian-style ceramics, in his style and techniques, and in his qualities as an artist reflected in them, had enormous impact on modern ceramics in the West.9 His work from his English period is characterized by designs and forms in the manner of old English pottery, Cizhou ware from China, and overglaze enameled Goryeo ware from Korea. But even more important was that he showed techniques such as iron glazes (No. 22), wax resist (No. 25), and hakeme (No. 31) that comprise his style as devices, as modes of expression still vital at that time. Hamada Shoji, as a creative artist, left a powerful stamp on the world of European and American ceramics.

There was a gap, in stance and thought, between Leach, whose ideal was the artist craftsman, and Murray, who engaged in ceramics as an artist. (That their lineages coexist is one of the appealing aspects of English studio pottery.) Yet in terms of design, they were of the same generation, having discovered their criteria for beauty in the exotic other. They developed abstract concepts for which Hamada and East Asian ceramics were the catalysts.

In the latter part of his career, Leach made monochromatic wares, using black or white glazes, for example, his basic approach, and few of those works are outstanding in form. Vase with combed decoration (No. 49), which he is thought to have produced at Onda, with its flowing form and straightforward hakeme, recalls the medieval pitchers that he mentions in A Potter's Book. Vase with ridged decoration, white porcelain (No. 55) dates from near the end of his life; it mixes a rustic yet delicate quality. Where Leach arrived in his last years reminds one of his observation that the most beautiful pots in the world are filled with technical imperfection.10

Today, the Leach Pottery is called the foundation of contemporary British ceramics. In this exhibition, we introduce William Marshall and other potters who sustained the Leach Pottery in its early years, of whom Michael Cardew and Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie were particularly outstanding.

Michael Cardew, Leach's first apprentice, had been familiar with pottery made by the English potter Fishley as a young man. In contrast to the Leach Pottery's emphasis on stoneware in the context of East Asian ceramics, Cardew shifted to making old English pottery, particularly slipware, his ideal. Inspired by vintage works from his native country, his stance as a contemporary pottery was to question what the "Englishness" of pottery is and what English ceramic traditions are.11 He produced, in a sense different from Leach, many followers.

Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, building on the techniques she learned from Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke, experimented extensively with her own ash glazes. Significantly, her artistic motivation was not the admiration for Chinese ceramics or old English pottery visible in the previous generation but her rejection of copying and grasp of the subtle states and colors of glazes as her true-to-life means of self expression. Pleydell-Bouverie pursued ceramics as her life work, not as a means for making a living or commercial purposes; a certain amateurism underlay her approach. Unwavering artistry anchored her pure exploration of a creative terrain free of self effacement.

Ceramics, made by firing its material, clay, essentially entails the question of how to make this weighty material, clay, stand up. A standing form is the essence of ceramics, and the artist's individuality is lodged in how he makes the clay stand up. In the mid twentieth century, ceramic expression in Britain took new directions, thanks two three potters who were originally from continental Europe.

The major distinctive feature of Lucie Rie's vessels is that, in them, she combined parts thrown on the wheel.12 Division into parts in the production process could have an aspect of seeking efficiency with mass production as its goal. In Rie's case, however, it was connected to the intensity of her pursuit of form. That is, it alleviated the softness of the line produced on the wheel, giving forms greater sharpness. Hans Coper also made vessel forms in which he combined geometrical, wheel thrown, parts his identity. Both were stimulated by ancient artifacts to achieve eternal forms with primitive beauty as their starting points. While Rie presents color as an element of design, Coper pursued texture and materiality in his monotonic works.

The Modernism that Rie and Coper introduced expressed itself in their use of the combination method to compose their vessels. The concept of combination both makes us anticipate the birth of expressive vessels as sculptural forms and also, through "combination" as placing vessels side by side, to sense the potential to develop into installations made of vessel-form works.

Ruth Duckworth began her career as a sculptor and was greatly influenced by Henry Moore and Brancusi. After various twists and turns, she ended up studying ceramics with Dora Billington and others at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London. At that time, the school kept its distance from the Leach style as its faculty and students explored the ideal form of ceramics. Duckworth, a sculptor, worked with clay as her material throughout her life. While small in size, her ceramics demonstrate an orientation to sculptural forms. During her time in Britain, she produced series of domestic wares (No. z75). After moving to the United States, she became active as a ceramic sculptor.

After the war, British art schools that taught ceramics not as industrial design but as a craft flourished, producing many studio potters.13 Meanwhile, not only the Leach Pottery but also Dartinton, Wenford Bridge, Winchcombe, and other regional pottery centers were training potters. In general, contemporary British ceramics was splitting into two groups. One was the "ethical pots" lineage, exemplified by the Leach school, that took as its standard a healthy beauty and the correct approach to making ceramics, with East Asian ceramics and old English pottery as its background. But even that lineage was not monolithic.

At the Leach Pottery, David Leach, who had taken on its management, introduced mail-order sales of its Standard Ware, inexpensive pottery for home use, while the training system that Janet Leach launched sought to meet contemporary demands while carrying on Bernard Leach's designs. Hamada Atsuya, Funaki Kenji, and Ichino Shigeyoshi were among the potters engaged in the international exchanges that continue to give the Leach Pottery its distinctive character today. With Janet Leach, given her knowledge of sculpture, at the Leach Pottery, the expressive creation of everyday pottery, exemplified in the work of John Bedding and Jason Wason, keeps alive the artistic side of the Leach Pottery.

Bernard Leach's "orthodoxy" is a spirit that has perhaps been carried on to a greater degree on the outside of the Leach Pottery. In John Leach and Richard Batterham, who is absorbed in firing his stout vessels in a diesel kiln, that craftsman posture lives on.

An artist who appreciates East Asian ceramics from a contemporary perspective is Phil Rogers, whose admiration for Hamada Shoji and his research on Hamada's work and his historic context is reflected in his own work. Lisa Hammond is not strictly a member of the Leach school, but inspired by the aesthetic of Mino ceramics, she fires her Shino and soda glazed works in a wood-burning kiln.

Svend Bayer, who studied with Michael Cardew and is part of a lineage carrying on his spirit, creates unaffected, vigorous ceramics, firing them in a wood-burning kiln. Clive Bowen is reviving traditional English slipware and presenting creative techniques in slip, similar to Hamada Shoji's slip trailing.

Here in the twenty-first century, quite a few potters creating everyday wares can be found in northern and southwestern England (No. 96-104). They find the rich natural environments in which they work a direct source of inspiration and express their feelings of awe for nature in their motifs. Making generous use of colored slips, they produce many realistic, painterly works in a style that carries on a distinctively English approach to nature and decoration that goes back to William Morris. The history of Studio Pottery, capitalized as the name of a school, has developed as an abstraction in clay. But as a more informal ongoing current, it can be seen to extend throughout the range of British pottery.

Another lineage that cannot be omitted in discussing contemporary British ceramics consists of the modernists who studied with Rie and Coper, among others, at art schools. In the 1970s and 1980s, what is known as the New Ceramics generation appeared and continues to diversify its styles. In the 1980s, the notion of the "vessel" was reinterpreted both in form and philosophically. Gordon Baldwin, Alison Britton, Carol McNicoll, Ken Eastman, and Magdalene Odundo are among the many talented potters at work today. Elizabeth Fritsch, who is introduced in this exhibition, has proposed new ways of viewing the nature of the visual and three-dimensional qualities of the vessel form. Martin Smith poses the question of the spatiality that the vessel prescribes. Tina Vlassopulos conveys the sensations she receives through all her senses by means of the vessel form. Jennifer Lee, who is in the lineage of Fritsch and her colleagues, quietly continues to develop her work in the twentyfirst century. The deep layers of potters' memories, the mandala they can touch with their fingertips are expressed through the layered colors of their clays and the shapes of their vessels

While English studio pottery has these two lineages, what makes it such a delight today is that their cornerstones—wares for practical use or for appreciation, functional or sculptural qualities, vessels or objects—are not opposed but coexist. Many potters work in a style that cannot be defined as belonging to either lineage or that has qualities of both. That, I believe, is because in mainstream British ceramics, works have generally not grown mammoth or architectural in nature. These potters respect the craft-art thinking in the details of their works, the physical thinking and technical sophistication that starts with their materials and techniques.

Walter Keeler and Jack Doherty are exploring the physical effects of salt and soda glazes, seeking rightness in clay forms, and creating powerfully expressive vessels. Materials frolic like abstract painting above the vessel, their materiality acting on the viewer. Dylan Bowen, who has added his contemporary interpretations to slipware, skillfully incorporates its effects as his style.

From the 1990s on, cooperative studios, where artists working in different genres share a place to work, have sprung up widely in London. Edmund de Waal and Julian Stair used to share the Vanguard Court Studio in South London. Both added philosophical thinking, in both language and in making, to the vessel, bringing about a new phase in English studio pottery. While making pots as usual, they presented their vessels as installations.14 The probability that a vessel is a vessel, the physicality that accompanies the ceramic arts, the nature of the group and individual memories that ceramics call up: they question them all. Of things exactly as they are (No. 119), de Waal say it is a symbol of his own experience encountering porcelains in Japan. Stair's Five Teapots and Caddies on a Ground (No. 120), raises the question of the presence of the everyday vessel and of the pedestal. Both potters are now showing their work in galleries around the world and are positioned in the context of contemporary art. Significantly, however, neither chose clay as his material for conceptual reasons. Rather, both extract their concepts from the pottery and the vessels. Thus, elegance as an object that is the source of concepts, beauty as a meticulous craft art are the major premises being bringing their work into existence. The elegance of the details is directly connected to deepening the heart of the work. Here the possibilities to overcome the matters between art and craft, which were the starting-points of the studio pottery, will appear.

The potters who taught them were studio potters who carefully produced vessels in which craft-like thinking lived. Chris Keenan discovered the night sky and the colors of the heavens in tenmoku and celadon glazes and creates playful porcelains in which vessels frolic together. Carina Ciscato, inspired by groups of buildings in Brazil, her native country, combines wheel-thrown parts to build vessel forms as constructions. Sun Kim makes effective use of the nature of the clay to present, quite richly, a sense of freshness and just the right sense of tension in her forms.

This essay provides an overview of trends in British studio pottery. The exhibition's purpose is to consider Hamada Shoji and Bernard Leach, individual potters in Mashiko and England, in parallel. It is not designed to cover the history of ceramics in England. Here I have focused on changes in the style of the vessel as a clue to understanding several of the works in this exhibition. East or West, ancient or modern, the vessel, whether an everyday ceramic vessel or a creative object, is "a symbol in the ceramic arts connected with the history of ceramics and many different cultures."15 Examining how its maker has addressed the vessel connects us to the heart of that ceramic art.16

When examining changes in the expression of the vessel in English studio pottery, issues related to values surface: how the potter's consciousness appears, whether East or West in origin, the expressiveness of glazes, the formative qualities of the vessel, the view of nature. These issues are not merely characteristics of English studio pottery; they are topics common to modern and contemporary ceramics as a whole. The Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art has, through twenty-five years of programs (and especially in the past decade), addressed, little by little, English studio pottery in terms of its connections with the local history of pottery in Mashiko. This exhibition introduces the collective results. The history of pottery in Mashiko is both the history of local ceramics and is also connected to the history of ceramics in modern Japan and to trends in ceramics in other countries as well. Mashiko is uniquely open to the world. How are the events in one person's life or in one region connected to the formation of the history of the world: this exhibition will be, we hope, an opportunity to consider that question anew.

(Curator, Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art)

Notes

| 1 | The vision of a "marriage of East and West" is reflected in the three steps of the creative process: consulting ceramics ancient and modern, from the East and the West, interpretation, and integration (marriage). Susuki Sadahiro, Bernard Leach no shogai to geijutsu (Bernard Leach's life and art). (Tokyo: MInerva Shobo, 2006), pp. 213-243. Edmund de Waal, Bernard Leach. (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1998), pp. 13-15 |

| 2 | Edmund de Waal, Bernard Leach. (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1998), pp. 13-15. |

| 3 | "The word 'pattern' really means original motif in the sense of exemplar, and not its repetiton, or copy." Bernard Leach, A Potter's Book. (London: Faber & Faber, 2011), p. 101. |

| 4 | In addition to the Martin Brothers, discussed later, they include William de Morgan, Christopher Dresser, and Omega Workshops led by Roger Fry. |

| 5 | For the influence of the Japanese tea wares, I thank Moira Vincentelli for this reference: Malcom Haslam, The Pursuit of Imperfection: The appreciation of Japanese teaceremony ceramics and the beginning of the Studio-Pottery movement in Britain, The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 – the Present, No.28, ARTS & CRAFTS ISSUE, pp.148-171, 2004. |

| 6 | See Emmanual Cooper, Nishi Maya, translator, Japanese translation of Bernard Leach: Life and Work. (Tokyo: Hus-10, 2011), p. 159. |

| 7 | Sarah Riddick, Pioneer Studio Pottery The Milner-White Collection. (London: Lund Humphries, 1990), p.11 8. |

| 8 | Maezaki Shinya, "Bernard Leach no kama wo tateta otoko—Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke no Eikoku ryugaku (1) (The man who built Bernard Leach's kiln— Matsubayashi's studies in England (1)," Mingei no. 717, 2012. |

| 9 | For the importance of Hamada Shoji in the early formation of studio pottery, see Julian Stair, "The Spark that ignited the flame—Hamada Shoji, Paterson's Gallery, and the birth of English studio pottery," Ceramics, Art, and Cultural Production in Modern Japan. (Norwich: Sainsbury Institute, 2020). |

| 10 | Bernard Leach, op. cit., p.24. |

| 11 | Victor Margrie contributed the following words to a special issue on Cardew's followers: "Was he an emissary of the glories of English slipware now past and forgotten, or was he the true guardian of an English pottery tradition which was to be preserved and extended into the present?," from "Michael Cardew – Pioneer Potter," Ceramic Review, No. 81, May-June 1983, p.12. |

| 12 | Kaneko Kenji, "Lucie Rie sakuhin no gensen (Sources of Lucie Rie's work)," Lucie Rie, Vol. 2. (Tokyo: Mitochu Koeki, 2007). |

| 13 | For postwar studio potters, see Oliver Watson, Studio Pottery. (London: Phaidon Press, 1994). |

| 14 | An early example of turning vessels into an installation is work by Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, who is not included in this exhibition. Inspired by Giorgio Morandi's still lifes, she lined up her vessels as in a painting. |

| 15 | Miura HIroko, "Miseru 'utusuwa' to iu shinboru (The fascinating vessel as symbol)," Utsuwa dormachikku ten (Dramatic vessels), exhibition catalogue. (Shigaraki: Shigaraki Cultural Park, 2017), pp. 181-84. |

| 16 | For a recent exhibiton on British studio pottery from the vessel type perspective, see Things of Beauty Growing: British Studio Pottery. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017). |

*"No." means plate numbers in the exhibition catalogue

[Acknowledgment]

This research was partially supported by The Satoh Artcraft Research & Scholarship Foundation.

The schedule might change depending on future circumstances. Please check the museum website, facebook and twitter for the latest information.